Trivia: Human Motion Control of Quadrupedal Robots Using Deep Reinforcement Learning

I wanted to share some side stories here that didn’t make it into the paper. I actually started this research almost six years ago and wrapped it up about four years ago, but a lot of my personal thoughts couldn’t go into the paper. Research papers have to be written in a very polished, formal way, so all the trial and error, the dumb mistakes, and the random thoughts that popped into my head along the way just get filtered out.

So here, I want to unpack some of those things. This won’t be a super well-organized story. I’m just going to write whatever comes to mind. The real reasons I got into this research, the kinds of conversations that happened along the way, and the behind-the-scenes stuff. There will be some thoughts about the results too, but this is more about the process and the personal context around it.

Why did I do this research?

These days, humanoid robots are doing backflips, so my paper can look a bit outdated. We already have robots that walk and run like humans, so human–humanoid teleoperation seems more important. You might even wonder whether we still need quadrupedal robots at all.

But I still think quadrupedal robots have real practical advantages. Structurally, they’re more stable, they adapt better to terrain, and they have good load-bearing capacity for their weight. In rough terrain, disaster sites, and outdoor environments, they can actually be a more realistic choice than humanoids. And if my work were pushed further, it could be applied to robots with completely non-human forms, like insect-like robots. No matter how much humanoid technology advances, I think those kinds of robots will still have their own strengths and use cases.

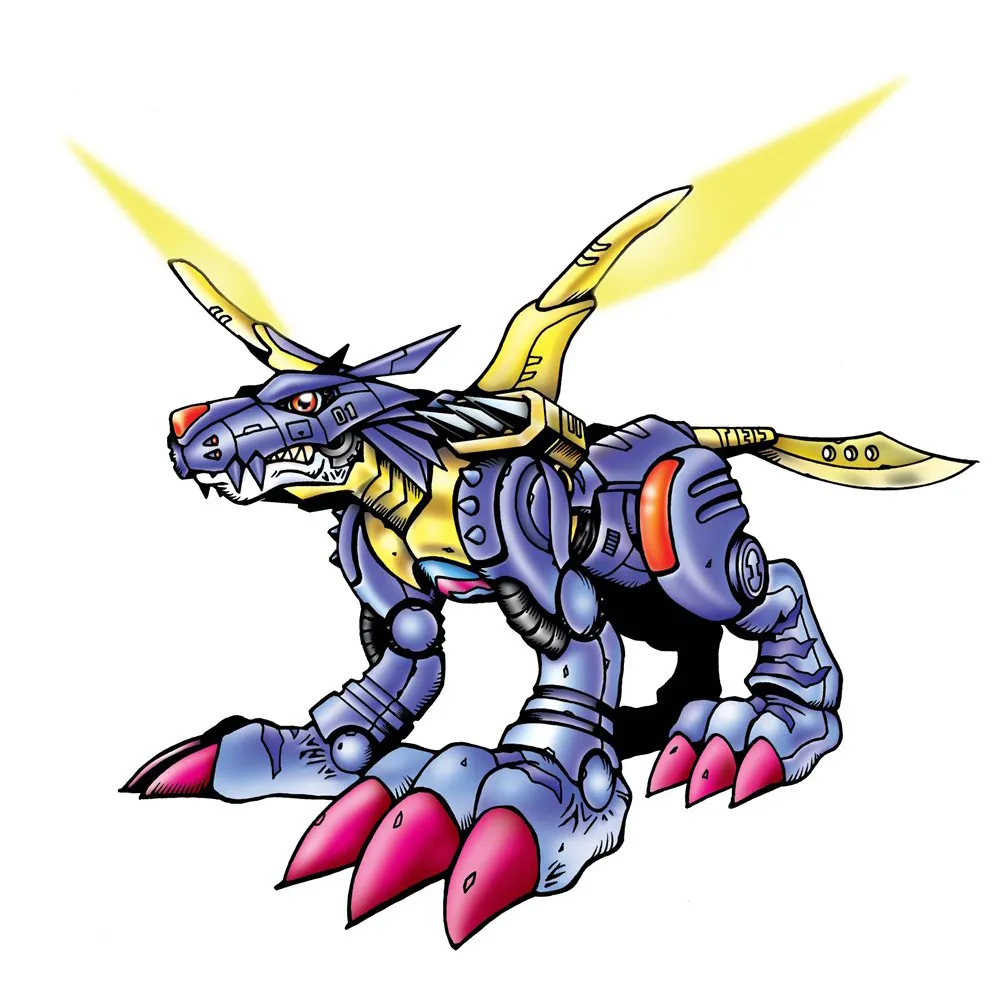

There was also a very personal reason for this research. I really love Digimon. In Digimon Tamers, when a Digimon reaches its ultimate form, the human fuses with it and controls it directly. When the human attacks, the Digimon attacks. When the human walks, the Digimon walks. And sometimes I’d imagine: in Tamers, most ultimate forms evolve into humanoid Digimon. But what if they didn’t?

For example, if Matt from Digimon Adventure had to fuse with MetalGarurumon and control it, how would he move? He wouldn’t walk like a human. He’d have to run on four legs, shake his head, and constantly balance himself. The control method, the sensation, and the interface would all be completely different.

When I first heard this research topic from Professor Sehoon Ha, I was thinking along those lines. The idea of naturally controlling a being with a completely different body, understanding its motion, and designing control methods that fit that form brought back some childhood curiosity. I think that’s why I had so much fun doing this research.

In the end, I approached this work as a question of how to intuitively control a system with a body completely different from a human’s, and how to make it move naturally. And I still think that question has real value.

Who should imitate whom?

Early in the project, I talked with Sehoon, who was advising me at the time, about control methods. He suggested that for precise control, the human should imitate a dog. Literally crawling on all fours, swinging their arms, and moving like a dog. Personally, I thought that if the meaning of the motion was similar enough, the result would be similar too. But since he suggested it, I decided to actually try it at home and see what would happen.

In my tiny studio apartment, I seriously hypnotized myself into thinking “I am a dog,” crawled on all fours, and swung my arms around. But it was way harder than I expected, and it didn’t feel intuitive at all. I’d been walking on two legs my whole life since I was three, and getting back the intuition for four-legged motion was not easy. More than anything, it felt like a violation of human dignity. I had a moment of, “Why am I doing this?”

So at the next meeting, I told him honestly:

After that, the direction of the research settled on controlling a quadrupedal robot using bipedal human motion. To be fair, the system I built would scale pretty well as long as you prepared the right data, whether you crawled on all fours or stood on your head. But for the demo in the paper, I chose the version where you stand on two legs and control the robot.

Can a quadrupedal robot walk on two legs?

This is something I really would have tried if I’d continued this research. But a bunch of things happened, and because of my military service, I ended up joining a game company, NCSOFT. So sadly, I couldn’t explore this direction further.

Back then, I talked about this idea with a friend I met at RSS conference on 2022. He was doing his PhD at MIT and doing quarupedal research. I told him, “Wouldn’t it be fun if a quadrupedal robot stood on two legs and did teleoperation? I even want to try making it box while standing on two legs.” He was pretty skeptical. He thought that because of the motor structure in a quadruped’s legs, you’d get gimbal lock issues and that balancing would be practically impossible.

I had a slightly different opinion. Standing still would be hard, sure, but if the robot kept stepping lightly, it might be more feasible than it sounds. In the end, both viewpoints were meaningful, and just having that kind of conversation was really fun.

Then about a year later, Sehoon published a paper with other researchers showing a quadrupedal robot standing and moving on two legs. The robot moved in a way pretty close to what I had imagined.

TWiRL: Learning and Adapting Agility Skills by Transferring Experience

As far as I know, even now, there’s still almost no research on teleoperating a quadrupedal robot using human motion while it stands on two legs. So if someone wants to continue this line of work, I think this direction is genuinely interesting. Imagine a quadrupedal robot boxing on two legs and then dropping back down to walk on four. The potential applications are wide, and it’s just fun. Hardly anyone has really done it yet. If someone wants to revive this idea, I’d welcome it, and I’d be happy to do a light co-work or share ideas.

How should we map the motions?

This is one of the questions I get asked the most about this research. And there’s a story behind it.

At first, I thought about introducing very strict mapping functions from human motion to quadrupedal robot motion. I tried IK and RBF-based methods. But once the semantics get even a little more complex, the number of things you have to consider just explodes. The more mapping rules you add, the more exceptions you get, and the more tuning points appear.

Then, my primary supervisor, Professor Jehee Lee came up with an idea: instead of strict mapping rules, use a “soft,” fuzzy mapping with a neural network. It sounds obvious now, but back then it felt like getting hit in the head. So what if the mapping isn’t exactly the way I want it? This is teleoperation. It’s meant to be an intuitive controller. If I stretch my arm and the robot goes a bit farther than I expected, I can just stretch a bit less next time. Whether it’s off by a few centimeters to the left or right doesn’t really matter. This wasn’t a task where exact mapping was critical.

So then the question became: how do we build a dataset that produces a controllable mapping with the minimum amount of data?

The idea was simple. If we just sample a few poses at the extremes of the motion range and a few transition motions in between, and feed those to the network, the network will infer the middle reasonably well.

For example, in a task where you stretch your arm, if you map the maximum stretch a human can do and the maximum stretch allowed by the robot’s range of motion, the in-between swinging motion should come out roughly okay. And in practice, it did. Of course, I didn’t literally use only those data points. There was quite a bit of heuristic tuning and extra data collection. But that was the core idea.

The key point was this: even if the mapping is a bit loose, you can still control the robot just fine if you use your body well. This wasn’t a precise numerical matching problem. It was closer to a human–robot interface problem.

Interesting walking patterns

While doing this research, I also discovered some unexpectedly fun walking patterns. I wanted the quadrupedal robot to handle a wide range of locomotion inputs in a physical environment, so during training, I deliberately randomized the gait parameters of the reference motion. Things like body height, foot clearance height, and swing angle.

Instead of making it follow just one pattern per episode, I randomly changed these parameters periodically during training.

What surprised me was that even when I changed them at a fairly fast rate, the robot still walked pretty stably. It felt like, “Wow, it works?”

Even more surprising was that this worked not just in simulation but on the real robot too. On the real hardware, I set the walking pattern to change every 3-5 seconds. The robot wobbled a bit, but it kept walking without falling. Both of my advisors were like, “Wait, this actually works?”

That’s when it really hit me: hardware has become way more robust than we used to think. In the past, random changes like this in gait parameters would’ve made the robot fall immediately. But now we’re at a point where you can run pretty aggressive experiments and the robot still holds up. That moment stuck with me.

Closing Thoughts

When I think about myself back then, it’s still a bit embarrassing. I was a complete beginner who didn’t know anything, and yet Professor Sehoon guided me and helped me turn this into a paper. I feel both sorry and deeply grateful to him. I wouldn’t say I’m a good researcher even now, but at least I’ve reached a point where I know what I don’t know. Back then, I was literally a blank slate. I didn’t even know what I didn’t know. Looking back, I’m even more thankful that he personally guided me through research in that state.

I’m also grateful to Professor Jehee, who boldly supported me when I said I wanted to be co-advised by Professor Sehoon, even though I had no idea what I was doing at the time. Including my time at NCSOFT, I ended up being under his guidance for almost six years. Every time, I’m impressed and surprised by how he always hits the core of the problem with his insights. It’s something I really want to emulate, but it doesn’t feel like the kind of depth you build in a day or two.

What I really gained from this research wasn’t just the final result. It was a sense for how to start a project, how to mess it up, and how to fix it and keep going. None of that appears in the paper, but personally, it’s become a pretty valuable asset.

And as for human–humanoid teleoperation, I still have more thoughts about that. I’d like to organize them and share them someday when I get the chance. It’s a different direction from this research.

Reference

Dukemon evolution: http://stream1.gifsoup.com/view1/1561404/digimon-evolution-o.gif

Metal Garurumon: https://digimon.net/reference_ko/detail.php?directory_name=metalgarurumon